Thread #16898889 | Image & Video Expansion | Click to Play

File: Screenshot 2026-01-25 141728.png (14.8 KB)

14.8 KB PNG

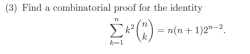

Hello, Im the anon that has been posting questions about combinatorial problems from time to time. If someone could explain to me a solution to this one it would be very nice, as it is important for later exercises and there is no answer for it.

My intuition led me to think that we are counting the number of ways one can choose a president, vice-president and a team for them to lead, with the nuance that the president can also be the vice-president, but I deeply feel like that is wrong.

The exercise is from the book "a walk through combinatorics", chapter "the binomial theorem", under Quickcheck.

21 RepliesView Thread

>>

>>

>>

>>

>>

>>

>>

>>16898889

Your intuition is right. You can either choose the full team and then select the president/vice-president from that team, or you can choose the president/vice-president first and then the rest of the team from those that remain.

>>

>>16898889

Well OP, I too cannot solve this alone so I just looked it up online. Why are you wasting time hoping for someone ONLINE to give you the solution when you can literally look it up ONLINE yourself?

If you're looking for a hint, I'll show you what the algebraic proof of solving this would be. It doesn't directly give any intuition for a combinatorical rationale, but there is a connection that I'll spell out for you.

The main takeaway you should get out of solving this problem is that you need to develop a certain type of intuition when you see objects of algebra that looks like this, an intuition I had to look up to even know this was even a thing. I'm guessing this is indeed a simple af problem, but only to those who've seen the connection already and thus have the intuition.

The algebraic proof is simple enough: start with f(x) = (1+x)^N, and write out the expansion with binomial theorem.

>So we get a summation that has N choose K times something, which in this case is x^k.

Straight up, it should be obvious that if we set x to be 1, we should end up with the obvious 2^n = sum of binomial coefficients.

It turns out it's easy to solve for the summation of (N choose K) times K times x^K or x^{K-1}. Simply take the derivative of f(x), and voila! It just pops right out with minimal effort. Set x = 1, and it's easy to see that the summation equals N2^{N-1}. When you write it out, do understand the importance of the algebra between turning x^{K-1} to x^K, even though x will go to 1, still matters when doing derivatives

cont.

>>

>>16899331

It should be intuitive now that we should differentiate both sides again to get something like a K^2 (N choose K) x^K, or K(K-1)x^{K-2}, or anything similar in between

All higher derivatives for f(x) never require chain rule because we aren't multiplying any x's together. But what if you were doing something different like changing x^{K-1} to x^K? Then this means multiplying x's to both sides, so any augmented f(x) or derivatives requires chain rule. Notice further

>that the solutions for the summation of K^2 (N choose K) x^K and K(K-1)x^{K-2} ought to be very similar, since they're only off by a term involving a lower polynomial of K

>but we already figured out how to do lower K polynomials!

Regardless on what polynomial of K you're trying to solve the summation for, there are always multiple terms that you're adding together, terms that are simple to directly solve for.

This is basically saying that if we just do f(x) and it's derivatives,

>we're deconstructing a polynomial with a basis (linear algebra, but super simple here) with K, K(K-1), K(K-1)(K-2), etc.

Please, do this in a pencil and paper before trying out a combinatorics proof. Derivatives are super easy so you should get a direct proof in like 3 or 5 minutes easy.

Now what about a combinatorics proof? Well, we've just learned that the solution can always come about by deconstructing the polynomial with the right polynomial basis. Are these deconstructed polynomial summations easier to interpret? What does sum K^0 (N choose K) mean as an example? What about sum K (N choose K) mean as an example? What about K(K-1)...?

(btw I only looked for a direct proof online; generalizing was me, even though it wasn't that hard to do)

>>

>>16899331

>>16899335

kys, autist

>>

File: 1757332883771621.png (362 KB)

362 KB PNG

>>16899018

Yes anon, I will look into it if I have the time, I really struggle with everything, but I find the topics interesting and sometimes even beautiful. I picked up combinatorics because I struggle with it the most from all of the precalc topics. I was thinking of looking into set theory, but maybe it would be better to go back to the most basic stuff and look into general problem solving.

>>16899123

This is a question I asked myself a lot too. It really is proving something using combinatorics. You show something by counting. Maybe you want to show that you are overcounting with the pigeonhole principle, or maybe you show that two sets are of the same size by finding a bijection between them. That is my understanding at least.

>>16899166

Thats good to know! summations somehow nag me, as its harder to see the whole picture and therefore harder for me to intuit what is going on in a given expression.

>>16899331

Thanks for taking the time anon, Ill look into your proof more later, as today is not a very good day for math for me. Btw what did you look for when you were looking for a proof, I did not exactly look for a solution online, but I did not see it listed as an identity on wikipedia or anything.

>>

>>16898936

I will add that xD has the combinatorial behavior of "distinguishing" an element.

The recipe basically enumerates the subsets of {1,...,n} then enumerates all ways to do 2 different distinguishments on each of those subsets.

>>

>>

>>

Suppose we want to determine how many [math] \$n\$ [\math] -digit binary numbers exist. The answer is straightforward: [math] \$2^n\$ [\math]. Simultaneously, we can count how many [math] \$n\$ [\math]-digit binary numbers contain exactly [math] \$k\$ [\math] zeros using the combination formula, [math] \$\binom{n}{k}\$ [\math]. Therefore, the sum of these combinations over all possible values of [math] \$k\$ [\math] equals the total: [math]\$\$\sum_{k=0}^{n} \binom{n}{k} = 2^n\$\$ [\math]

Think of it as a probability . [math] \$\binom{n}{k}\$ [\math] divided by [math] \$2^n\$ [\math] is the probability of drawing a binary number with exactly [math] \$k\$ [\math] zeros. OP's equation is expectation value of [math] \$k^2\$ [\math]

>>

I've fucked my shit up.

>>16903224

> Suppose we want to determine how many [math] n [/math] -digit binary numbers exist. The answer is straightforward: [math] 2^n [/math]. Simultaneously, we can count how many [math] n [/math]-digit binary numbers contain exactly [math] k [/math] zeros using the combination formula, [math] \binom{n}{k} [/math]. Therefore, the sum of these combinations over all possible values of [math] k [/math] equals the total: [math] \sum_{k=0}^{n} \binom{n}{k} = 2^n [/math]

> Think of it as a probability . [math] \binom{n}{k} [/math] divided by [math] 2^n [/math] is the probability of drawing a binary number with exactly [math] k [/math] zeros. OP's equation is expectation value of [math] k^2 [/math]

>>

>>16903224

>>16903226

Obviously, I didn't finish the thing.

However

It follows that the expectation value of [math]k/2[/math] (in other words, average) should be[math]n/2[/math

Thus

[math]\sum_{k=0}^{n} k\binom{n}{k} / 2^n = n/2[/math]

I think something similar should work for [math]k^2[/math]

>>

>>

>>16903228

>>16903230

Nah, [math]n/2[/math] is the correct answer, I checked using the binomial expansion and taking derivative of it. After all, average could be fractional.

>>

[math]k^2\binom{n}{k}[/math] = [math](k(k-1) + k)\binom{n}{k}[/math] =

[math]k(k-1)\binom{n}{k}[/math] + [math]k\binom{n}{k}[/math] =

= [math]n(n-1)\binom{n-2}{k-2}[/math]+ [math]n\binom{n-1}{k-1}[/math] =

= [math]n(n-1)\binom{n-2}{k-2}[/math]+ [math]n\binom{n-1}{k-1}[/math]

If you then sum over k, you get

[math]n(n-1)2^{n-2}[/math] + [math]n2^{n-1}[/math] = [math]n(n+1)2^{n-2}[/math]

>>

>>16899664

If you think about how the product rule of differentiation works for a product of monic linear terms, it is as if a "timeline" is generated for each way to "kill" one term of the product.

The "timelines" are implicitly indexed by which term was killed.

(x^k)' = 1*x^(k-1) + x*1*x^(k-2) + x^2 *1*x^(k-3) + ... + x^(k-1) * 1

=k*x^(k-1)

multiplying by x afterwards "revives" the "killed" term in each timeline. The effect of xD just generates a timeline for each term of the product with an implied index (the distinguishment) corresponding to which term was killed then revived in that particular timeline.

I hope it is easy to see how (1+x)^n enumerates the subsets of {1,...,n}.

Once you can see the matrix code, algebraic and combinatorial aren't really different adjectives.